Last Updated: 2019-07-19

Codelab Author: Jeremy Jacobson

This is a brief introduction to Linux which targets students learning cloud computing and programming. It presents select material from the excellent Introduction to Linux written by Machtelt Garrels. It was adapted into a codelab by Jeremy Jacobson.

What you'll learn

- What is Linux?

- Linux basics

What you'll learn

- What is Linux?

- Where and how did Linux start?

- Isn't Linux that system where everything is done in text mode?

- Does Linux have a future or is it just hype?

- What are the advantages of using Linux?

- What are the disadvantages?

- What kinds of Linux are there and how do I choose the one that fits me?

- What are the Open Source and GNU movements?

History

In order to understand the popularity of Linux, we need to travel back in time, about 30 years ago...

Imagine computers as big as houses, even stadiums. While the sizes of those computers posed substantial problems, there was one thing that made this even worse: every computer had a different operating system. Software was always customized to serve a specific purpose, and software for one given system didn't run on another system.

Unix

In 1969, a team of developers in the Bell Labs laboratories started working on a solution for the software problem, to address these compatibility issues. They developed a new operating system, which was

- Simple and elegant.

- Written in the C programming language instead of in assembly code.

- Able to recycle code.

The Bell Labs developers named their project "UNIX."

The code recycling features were very important. Until then, all commercially available computer systems were written in a code specifically developed for one system. UNIX on the other hand needed only a small piece of that special code, which is now commonly named the kernel. This kernel is the only piece of code that needs to be adapted for every specific system and forms the base of the UNIX system. The operating system and all other functions were built around this kernel and written in a higher programming language, C.

Linus and Linux

By the beginning of the 90's home PCs were finally powerful enough to run a full blown UNIX. Linus Torvalds, a young man studying computer science at the University of Helsinki, thought it would be a good idea to have some sort of freely available academic version of UNIX, and promptly started to code.

From the start, it was Linus' goal to have a free system that was completely compliant with the original UNIX. That is why he asked for POSIX standards, POSIX still being the standard for UNIX.

All the features of UNIX were added over the next couple of years, resulting in the mature operating system Linux has become today.

The User Interface

Is using Linux difficult?

Whether Linux is difficult to learn depends on the person you're asking. Experienced UNIX users will say no, because Linux is an ideal operating system for power-users and programmers, because it has been and is being developed by such people.

Everything a good programmer can wish for is available: compilers, libraries, development and debugging tools. These packages come with every standard Linux distribution. The C-compiler is included for free - as opposed to many UNIX distributions demanding licensing fees for this tool.

Open source

The idea behind Open Source software is rather simple: when programmers can read, distribute and change code, the code will mature. People can adapt it, fix it, debug it, and they can do it at a speed that dwarfs the performance of software developers at conventional companies. This software will be more flexible and of a better quality than software that has been developed using the conventional channels, because more people have tested it in more different conditions than the closed software developer ever can.

The Open Source initiative started to make this clear to the commercial world, and very slowly, commercial vendors are starting to see the point. While lots of academics and technical people have already been convinced for 20 years now that this is the way to go, commercial vendors needed applications like the Internet to make them realize they can profit from Open Source. Now Linux has grown past the stage where it was almost exclusively an academic system, useful only to a handful of people with a technical background. Now Linux provides more than the operating system: there is an entire infrastructure supporting the chain of effort of creating an operating system, of making and testing programs for it, of bringing everything to the users, of supplying maintenance, updates and support and customizations.

Properties of Linux

Linux Pros

A lot of the advantages of Linux are a consequence of Linux' origins, deeply rooted in UNIX, except for the first advantage, of course: Linux is free. No registration fees, no costs per user, free updates, and freely available source code in case you want to change the behavior of your system.

Most of all, Linux is free as in free speech: The license commonly used is the GNU Public License (GPL). The license says that anybody who may want to do so, has the right to change Linux and eventually to redistribute a changed version, on the one condition that the code is still available after redistribution. In practice, you are free to grab a kernel image, for instance to add support for teletransportation machines or time travel and sell your new code, as long as your customers can still have a copy of that code.

Linux Cons

"Quot capites, tot rationes", as the Romans already said: the more people, the more opinions. At first glance, the amount of Linux distributions can be frightening, or ridiculous, depending on your point of view.

When asked, generally every Linux user will say that the best distribution is the specific version he is using. So which one should you choose? Don't worry too much about that: all releases contain more or less the same set of basic packages.

Linux Flavors

Linux and GNU

Linux may appear different depending on the distribution, your hardware and personal taste, but the fundamentals on which all graphical and other interfaces are built, remain the same. The Linux system is based on GNU tools (Gnu's Not UNIX), which provide a set of standard ways to handle and use the system. All GNU tools are open source, so they can be installed on any system.

A list of common GNU software:

- Bash: The GNU shell

- Coreutils: a set of basic UNIX-style utilities, such as ls, cat and chmod

- Emacs: a very powerful editor

- GNU SQL: relational database system

Throughout this guide we will only discuss freely available software, which comes (in most cases) with a GNU license.

To install missing or new packages, you will need some form of software management.

RPM is the RedHat Package Manager, which is used on a variety of Linux systems, even though the name does not suggest this.

Yellowdog Updater Modified (YUM), which was originally developed to manage Red Hat Linux systems at Duke University's Physics department, is used, for instance, on Amazon Linux. YUM adds automatic updates and package management, including dependency management, to RPM systems.

The Debian Advanced Packaging Tool (APT) is used on Ubuntu. YUM is like APT in that it works with repositories, which are collections of packages and are typically accessible over a network connection.

In order to get the most out of this guide, we will immediately start with a practical chapter on connecting to the Linux system and doing some basic things.

What you'll learn

- Navigating through the file system

- Determining file type

- Looking at text files

- Finding help

Logging in, activating the user interface and logging out

Text mode

You know you're in text mode when the whole screen is black, showing (in most cases white) characters. A text mode login screen typically shows some information about the machine you are working on, the name of the machine and a prompt waiting for you to log in:

RedHat Linux Release 8.0 (Psyche) blast login: _

2.2. Absolute basics

2.2.1. The commands

These are the quickies, which we need to get started; we will discuss them later in more detail.

Table 2-1. Quickstart commands

Command | Meaning |

| Displays a list of files in the current working directory, like the dir command in DOS |

| change directories |

| change the password for the current user |

| display file type of file with name filename |

| throws content of text file on the screen |

| display present working directory |

| leave this session |

| read man pages on command |

| read info pages on command |

| search the whatis database for strings |

2.2.2. General remarks

Commands can be issued by themselves, such as ls. A command behaves different when you specify an option, usually preceded with a dash (-), as in ls -a. The same option character may have a different meaning for another command. GNU programs take long options, preceded by two dashes (--), like ls --all. Some commands have no options.

The argument(s) to a command are specifications for the object(s) on which you want the command to take effect. An example is ls /etc, where the directory /etc is the argument to the ls command. This indicates that you want to see the content of that directory, instead of the default, which would be the content of the current directory, obtained by just typing ls followed by Enter. Some commands require arguments, sometimes arguments are optional.

You can find out whether a command takes options and arguments, and which ones are valid, by checking the online help for that command, see Section 2.3.

In Linux, like in UNIX, directories are separated using forward slashes, like the ones used in web addresses (URLs). We will discuss directory structure in-depth later.

The symbols . and .. have special meaning when directories are concerned. We will try to find out about those during the exercises, and more in the next chapter.

2.2.3. Using Bash features

Several special key combinations allow you to do things easier and faster with the GNU shell, Bash, which is the default on almost any Linux system, see Section 3.2.3.2. Below is a list of the most commonly used features; you are strongly suggested to make a habit out of using them, so as to get the most out of your Linux experience from the very beginning.

Table 2-2. Key combinations in Bash

Key or key combination | Function |

Ctrl+A (ctrl+shift+c) | Move cursor to the beginning of the command line. |

Ctrl+C (ctrl+shift+c) | End a running program and return the prompt, see Chapter 4. |

Ctrl+D | Log out of the current shell session, equal to typing exit or logout. |

Ctrl+E (ctrl+shift+e) | Move cursor to the end of the command line. |

Ctrl+l (lowercase L) | Clear this terminal. |

Ctrl+R | Search command history, see Section 3.3.3.4. |

Ctrl+Z | Suspend a program, see Chapter 4. |

ArrowLeft and ArrowRight | Move the cursor one place to the left or right on the command line, so that you can insert characters at other places than just at the beginning and the end. |

ArrowUp and ArrowDown | Browse history. Go to the line that you want to repeat, edit details if necessary, and press Enter to save time. |

Shift+PageUp and Shift+PageDown | Browse terminal buffer (to see text that has "scrolled off" the screen). |

Tab | Command or filename completion; when multiple choices are possible, the system will either signal with an audio or visual bell, or, if too many choices are possible, ask you if you want to see them all. |

Tab Tab | Shows file or command completion possibilities. |

The last two items in the above table may need some extra explanations. For instance, if you want to change into the directory directory_with_a_very_long_name, you are not going to type that very long name, no. You just type on the command line cd dir, then you press Tab and the shell completes the name for you, if no other files are starting with the same three characters. Of course, if there are no other items starting with "d", then you might just as well type cd d and then Tab. If more than one file starts with the same characters, the shell will signal this to you, upon which you can hit Tab twice with short interval, and the shell presents the choices you have:

your_prompt> cd st starthere stuff stuffit

In the above example, if you type "a" after the first two characters and hit Tab again, no other possibilities are left, and the shell completes the directory name, without you having to type the string "rthere":

your_prompt> cd starthere

Of course, you'll still have to hit Enter to accept this choice.

This works for all file names that are arguments to commands.

The same goes for command name completion. Typing ls and then hitting the Tab key twice, lists all the commands in your PATH (see Section 3.2.1) that start with these two characters:

your_prompt> ls ls lsdev lspci lsraid lsw lsattr lsmod lspgpot lss16toppm lsb_release lsof lspnp lsusb

2.3. Getting help

2.3.2. The man pages

Reading man pages is usually done in a terminal window when in graphical mode, or just in text mode if you prefer it. Type the command like this at the prompt, followed by Enter:

yourname@yourcomp ~> man man

The documentation for man will be displayed on your screen after you press Enter:

man(1) man(1) NAME man - format and display the on-line manual pages manpath - determine user's search path for man pages SYNOPSIS man [-acdfFhkKtwW] [--path] [-m system] [-p string] [-C config_file] [-M pathlist] [-P pager] [-S section_list] [section] name ... DESCRIPTION man formats and displays the on-line manual pages. If you specify section, man only looks in that section of the manual. name is normally the name of the manual page, which is typically the name of a command, function, or file. However, if name contains a slash (/) then man interprets it as a file specification, so that you can do man ./foo.5 or even man /cd/foo/bar.1.gz. See below for a description of where man looks for the manual page files. OPTIONS -C config_file lines 1-27

Browse to the next page using the space bar. You can go back to the previous page using the b-key. When you reach the end, man will usually quit and you get the prompt back. Type q if you want to leave the man page before reaching the end, or if the viewer does not quit automatically at the end of the page.

In the previous section you learned important key combinations for bash. Use them to help you move faster in completing the following challenge:

Terminus

Play the game Terminus. Try to answer the following questions.

Where do you find the Pony?

What is the password to the AthenaCluster?

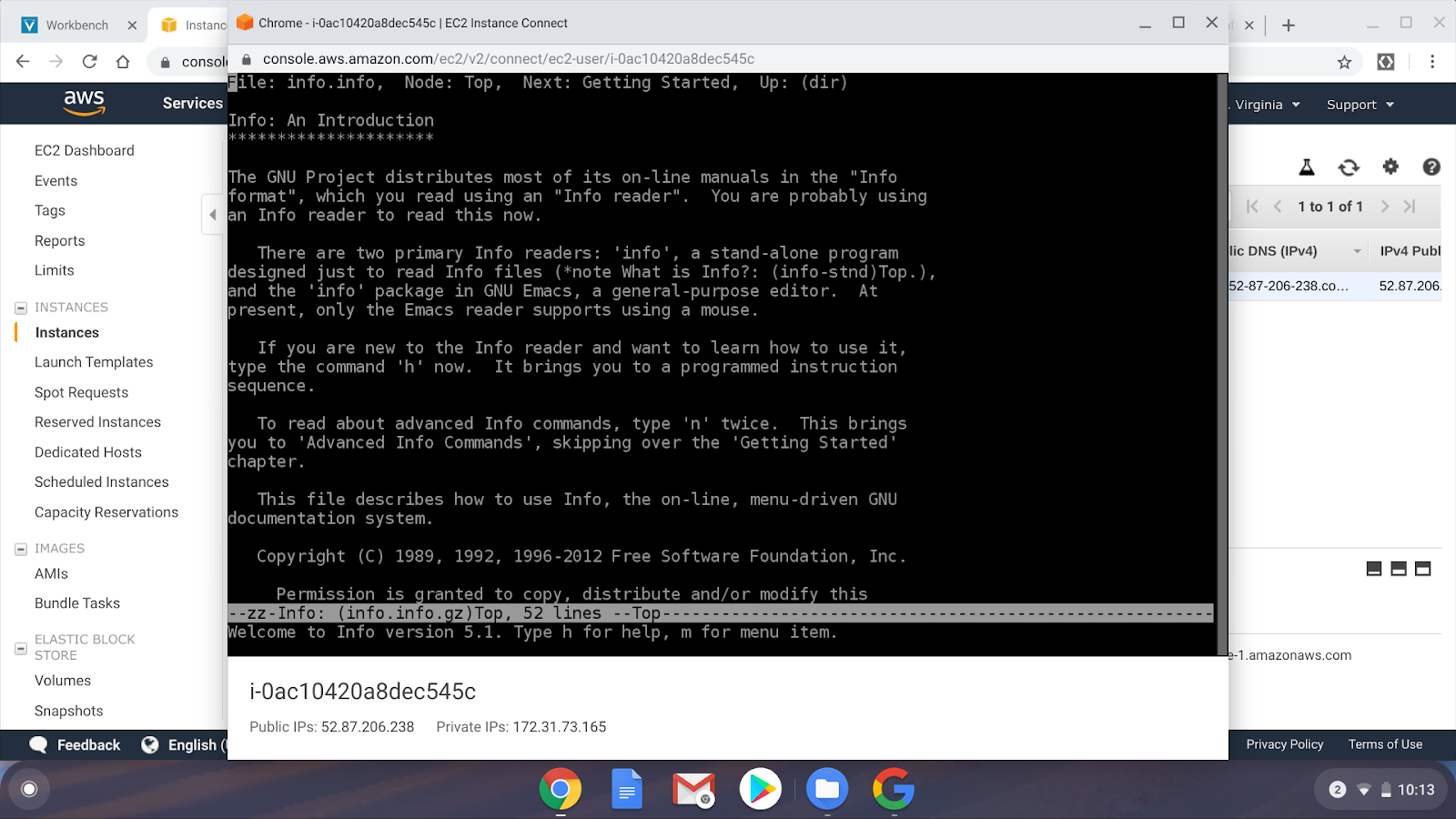

In addition to the man pages, you can read the Info pages about a command, using the info command. These usually contain more recent information and are somewhat easier to use. The man pages for some commands refer to the Info pages.

On your Linux machine at the shell prompt, simply type

bash$ info info

and then follow the prompts (e.g. type h...) to start the tutorial. You should see at the start

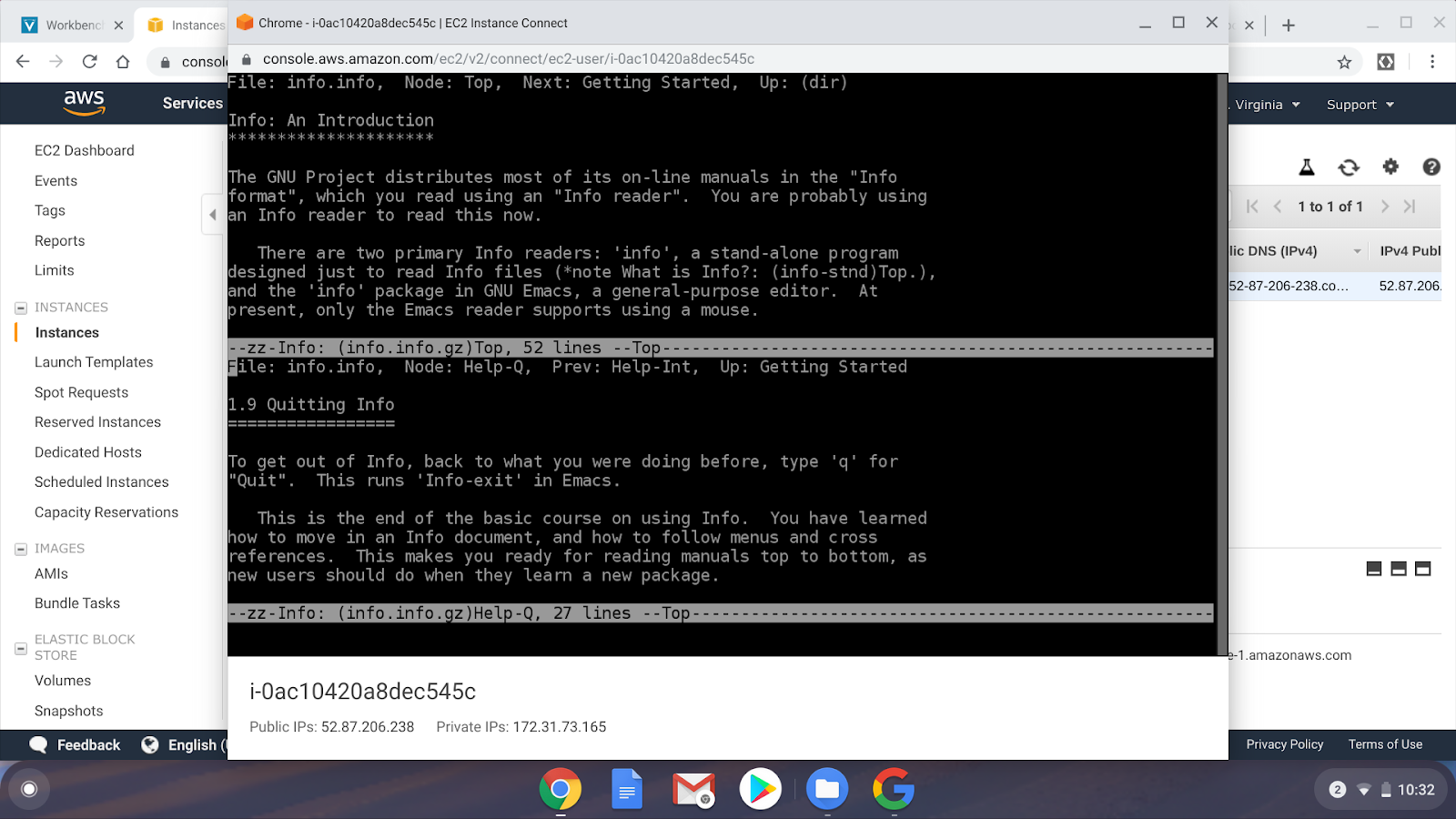

You should see at the finish

Which is not a way to convert lowercase letters to uppercase?

More info

The whatis and apropos commands

A short index of explanations for commands is available using the whatis command, like in the examples below:

[your_prompt] whatis ls ls (1) - list directory contents

This displays short information about a command, and the first section in the collection of man pages that contains an appropriate page.

If you don't know where to get started and which man page to read, apropos gives more information. Say that you don't know how to start a browser, then you could enter the following command:

another prompt> apropos browser

Galeon [galeon](1) - gecko-based GNOME web browser

lynx (1) - a general purpose distributed information browser

for the World Wide Web

ncftp (1) - Browser program for the File Transfer Protocol

opera (1) - a graphical web browser

pilot (1) - simple file system browser in the style of the

Pine Composer

pinfo (1) - curses based lynx-style info browser

pinfo [pman] (1) - curses based lynx-style info browser

viewres (1x) - graphical class browser for Xt

After pressing Enter you will see that a lot of browser related stuff is on your machine: not only web browsers, but also file and FTP browsers, and browsers for documentation. If you have development packages installed, you may also have the accompanying man pages dealing with writing programs having to do with browsers. Generally, a command with a man page in section one, so one marked with "(1)", is suitable for trying out as a user. The user who issued the above apropos might consequently try to start the commands galeon, lynx or opera, since these clearly have to do with browsing the world wide web.

The --help option

Most GNU commands support the --help, which gives a short explanation about how to use the command and a list of available options. Below is the output of this option with the cat command:

userprompt@host: cat --help

Usage: cat [OPTION] [FILE]...

Concatenate FILE(s), or standard input, to standard output.

-A, --show-all equivalent to -vET

-b, --number-nonblank number nonblank output lines

-e equivalent to -vE

-E, --show-ends display $ at end of each line

-n, --number number all output lines

-s, --squeeze-blank never more than one single blank line

-t equivalent to -vT

-T, --show-tabs display TAB characters as ^I

-u (ignored)

-v, --show-nonprinting use ^ and M- notation,

except for LFD and TAB

--help display this help and exit

--version output version information and exit

With no FILE, or when FILE is -, read standard input.

Report bugs to <bug-textutils@gnu.org>.

Exceptions

Some commands don't have separate documentation, because they are part of another command. cd, exit, logout and pwd are such exceptions. They are part of your shell program and are called shell built-in commands. For information about these, refer to the man or info page of your shell. Most beginning Linux users have a Bash shell. See Section 3.2.3.2 for more about shells.

Basic Linux commands

Command | Meaning |

| Search for information about a command or subject. |

| Show content of one or more files. |

| Change into another directory. |

| Get information about the content of a file. |

| Read Info pages about a command. |

| Leave a shell session. |

| List directory content. |

| Read manual pages of a command. |

| Change your password. |

| Display the current working directory. |

2.5. Exercises

Most of what we learn is by making mistakes and by seeing how things can go wrong. These exercises are made to get you to read some error messages. The order in which you do these exercises is important.

Don't forget to use the Bash features on the command line: try to do the exercises typing as few characters as possible!

2.5.3. Directories

- ▢ Enter the command cd blah

-> What happens? - ▢ Enter the command cd ..

Mind the space between "cd" and ".."! Use the pwd command.

-> What happens? - ▢ List the directory contents with the ls command.

-> What do you see?

-> What do you think these are?

-> Check using the pwd command. - ▢ Enter the cd command.

-> What happens? - ▢ Repeat step 2 two times.

-> What happens? - ▢ Display the content of this directory.

- ▢ Try the command cd root

-> What happens?

-> To which directories do you have access? - ▢ Repeat step 4.

Do you know another possibility to get where you are now?

2.5.4. Files

- ▢ Change directory to / and then to etc. Type ls; if the output is longer than your screen, make the window longer, or try Shift+PageUp and Shift+PageDown.

- ▢ Return to your home directory using the cd command.

- ▢ Enter the command file .

-> Does this help to find the meaning of "."? - ▢ Can you look at "." using the cat command?

- ▢ Display help for the cat program, using the --help option. Use the option for numbering of output lines to count how many users are listed in the file /etc/passwd.

2.5.5. Getting help

- ▢ Read man intro

- ▢ Read man ls

- ▢ Try man or info on cd.

-> How would you find out more about cd? - ▢ Read ls --help and try it out.

Congratulations, you're now familiar with Linux and some important commands.

Further reading

- Unix Shell Programming" by Stephen G.Kochan and Patrick H.Wood, Sams Publishing, ISBN 067248448X

- "Learning the Bash Shell" by Cameron Newham and Bill Rosenblatt, O'Reilly UK, ISBN 1565923472

Reference docs

- Introduction to Linux written by Machtelt Garrels.

- The Linux documentation project: all docs, manpages, HOWTOs, FAQs

- Ubuntu

* Copyright (c) 2002-2007, Machtelt Garrels

* All rights reserved.

* Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without

* modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions are met:

*

* * Redistributions of source code must retain the above copyright

* notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer.

* * Redistributions in binary form must reproduce the above copyright

* notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer in the

* documentation and/or other materials provided with the distribution.

* * Neither the name of the author, Machtelt Garrels, nor the

* names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products

* derived from this software without specific prior written permission.

*

* THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE AUTHOR AND CONTRIBUTORS "AS IS" AND ANY

* EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED

* WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE

* DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHOR AND CONTRIBUTORS BE LIABLE FOR ANY

* DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

* (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES;

* LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND

* ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR TORT

* (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS

* SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.